Wooooosh. That was the sound of a 68 MPH fast ball as it sailed over the middle of the plate, past my bat, and straight into the catcher's mitt. It was my first plate appearance in a regional Little League game and I had just struck out. With a lump in my throat, I began my walk back to the dugout, thirty seconds that felt like an eternity. My ego was bruised and I had let my team down.

As the game went on though, I realized I wasn't alone. I watched as each of my buddies faced similar fates. Our whole team went down swinging... everyone except Brian Goosey that is. In the last inning, he connected, sending the ball straight into stands for a home run and giving us a 1-0 game win keeping our hopes alive to reach the Little League World Series. It only took one swing to erase the goose egg that stood on the scoreboard. One swing to win the game.

Striking out is just part of the process

We learn the sting of failure early in life. You'd think it would get easier as we grow older and more accustomed to it, but it actually gets worse as our imaginations get even better at coming up with horrific (and grossly exaggerated) consequences of failure. This fear, however irrational, can be paralyzing. As adults we begin trying to minimize failure by any means necessary, carefully over analyzing every decision and always choosing the safest paths. The truth is, that this behavior is far scarier than anything failure could cause. It doesn't make us any safer or any more successful. In fact, it actually ensures that we won't achieve the potentially game changing results that only taking risks can achieve.

Failure is an integral part of design. Design requires making mistakes and working through a lot of wrong answers, often very publicly. It can be painfully revealing. It requires a vulnerability that many of our coworkers misunderstand, but it's one reason designers are better at using empathy as a way to create better product and service outcomes. On a daily basis, we're missing the mark in hundreds of small, incremental decisions that help our organizations get better results.

Companies know they need design, but they don't understand that mistake-making is one of its base elements, a key ingredient to its magic. So in a misguided effort to reduce what they see as risk, they institute rigid processes and other constraints. But the collateral damage is devastating. In addition to risk, they also reduce the growth and passion of their creative thinkers and the momentum of their business.

Playing it safe is natural

But the blame can't entirely be placed on companies and the critical thinking executives in them. Designers themselves, once they hit the big leagues of an executive role or title, often begin feeling that fear and vulnerability of "striking out." They start playing it safe, make a few bunts here and there, but nothing too wild. Nothing that runs the risk of spectacular failure... or spectacular success either.

Risk avoidance is a natural instinct, a defense mechanism built into us by our ancestors over millennia. In our collaborative environments, it's called collective avoidance motivation. So to reprogram our brains to ignore that, to actually embrace it, is no easy task. We not only have to adjust our approach, we need to facilitate a culture that supports more home run hitting. Critical thinkers will need to embrace more divergent thinking. Leaders will need to deal with failing and move on. Workers will need to figure out how to get over the discomfort of wrong answers.

We don't have to look far for inspiring examples of people embracing different approaches. I captured this recently in my thinking differently Apple post, but my favorite example is looking at how Babe Ruth changed baseball forever by focusing on home runs.

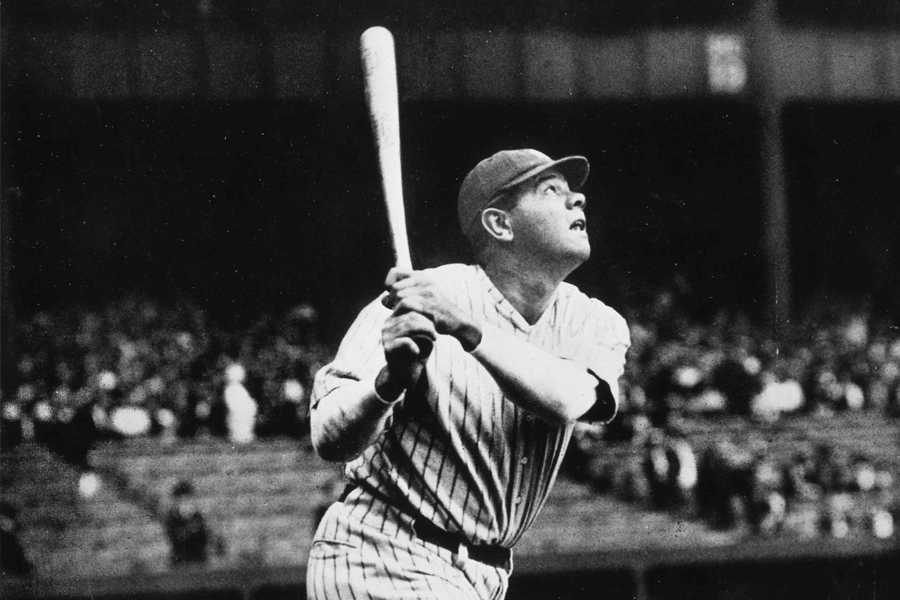

Swinging the bat to impress a new generation

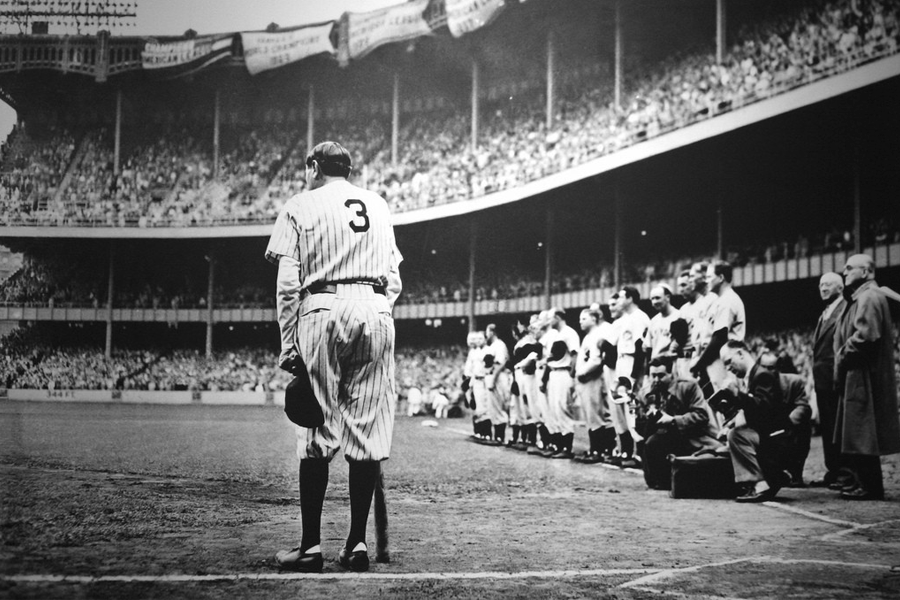

By the year 1923, Babe Ruth had redefined how baseball was played by setting the record for most home runs in a season with a power bat and a personality. What most people don't know is that he also set the record for most for most strikeouts for any player in Major League Baseball. Over his storied career he struck out 1,330 times, but overcame his failures to hit 714 home runs. He was a dynamic player that captured people's attention with his style of play.

In the previous two decades Ty Cobb stood on baseball's highest pedestal with a completely different approach. His lifetime batting average is still the highest of all time and he's credited with 90 MLB records. In 1923 however, baseball was looking for something different and Ruth represented the change in how baseball would be played. Getting singles was no longer what people wanted- they wanted to see the ball hit over the fence. "Cobb represents the mauve decades in baseball," said The Sporting News. "Ruth represents the hot cha-cha, and hey nonny, nonny period."

"Every strike brings me closer to the next home run," Babe Ruth once pined.

After enduring several years of seeing his fame and notoriety usurped by Ruth, Cobb decided that he was going to show that swinging for the fences was no challenge for a top hitter. On May 5, 1925, he began a two-game hitting spree better than any even Ruth had unleashed. Sitting in the Tiger dugout, he told a reporter that, for the first time in his career, he was going to swing for the fences. That day, he went 6 for 6, with two singles, a double and three home runs. The 16 total bases set a new AL record. The next day he had three more hits, two of which were home runs. Cobb wanted to show that he could hit home runs when he wanted, but simply chose not to do so. At the end of the series, the 38-year-old veteran superstar had gone 12 for 19 with 29 total bases and then went happily back to his usual bunting and hitting-and-running. For his part, Ruth's attitude was that "I could have had a lifetime .600 average, but I would have had to hit them singles. The people were paying to see me hit home runs." Even so, when asked in 1930 by Grantland Rice to name the best hitter he'd ever seen, Cobb answered, "You can't beat the Babe. Ruth is one of the few who can take a terrific swing and still meet the ball solidly. His timing is perfect. [No one has] the combined power and eye of Ruth." - Wikipedia

You've got it all wrong

"That's wrong. It's not the right answer." - said yesterday, and every day before that.

As a designer, we're used to hearing how our informed opinions are wrong. We frequently use abductive reasoning to arrive at solutions. We're used to helping our team figure out what does but also doesn't work. It can be discouraging, but as a designer I know my role isn't to dart to an answer, but rather, get my team seeking the best answers through iteration and collaboration. That means I must be willing to share wrong answers. In fact, my job doesn't really require me to have any right answers, instead, I must have ways to get to the right answer. As such, my job is to fail continuously to be able to hit home runs!

I've grown to accept that others may not understand this, even if I spend time explaining this to coworkers. I've been doing it for over two decades. Here's the deal though, if designers are going to play a role in helping their companies become more design centric, we need to figure out how to make these ideas stick. Otherwise we're just creating frustration, flatlining our career growth and stalling people's faith in design. Afterall, Babe had a .341 lifetime batting average, which meant he missed two thirds of the time!

Nobody hit a home run watching the ball

I've had my share of blank stares and arguments from my corporate coworkers, but it doesn't deter me from trying to create meaningful dialog about the challenges of using design to create better business outcomes. It can be tiring work and sometimes agonizing.

Designers need to persevere through the frustrations created by our methods and techniques to find better ways to effectively collaborate with our corporate, critical thinking partners. We need to have courage to stick with it to find harmony in our work styles. Perhaps I'm a little crazy, but as a designer, I find this an amazing opportunity to redefine our relationships in our organizations.

The game has forever changed. The demands placed on designers are absolutely staggering and the pace of technological advancement is mind-blowing. We simply can't afford to play it safe. The cost of inaction is too great, too risky. We have to swing, and swing hard if we want to win. And this means getting everybody okay with a few strikes, including ourselves. Because when we finally do connect, when we get it right and land that home run, any memories of our past strikeouts disappear into the deafening roar of the crowd. Swing for the fences.

Bryan Zmijewski

Leading the charge at ZURB since 1998

Our fearless leader has been driving progressive design at ZURB since 1998. That makes him quite the instigator around the offices, consistently challenging both the team and our customers to strive to always do better and better.

Learn more '

Follow him at @bryanzmijewski