Last year we set out to challenge what people believed to be Design Thinking. Since then we committed ourselves to defining a design methodology that pulled from our two decades of design knowledge. We realized that the lessons and methods we discovered since our beginnings in 1998 would make it easier for millions of designers to take advantage of our insights and help their design teams create more value in their organizations. We found that in Progressive Design.

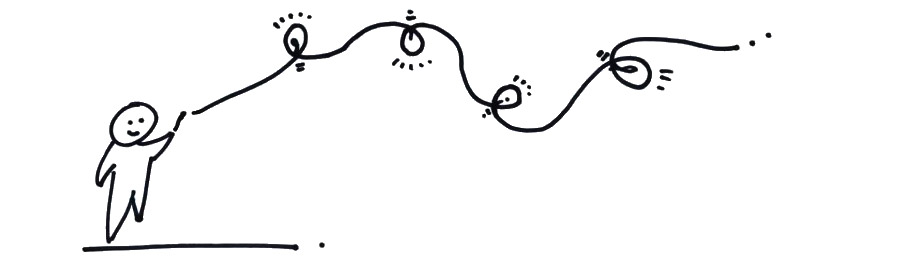

We've defined two principles of Progressive Design- Design for Influence and Lead by Design. In this blog post, we define our third principle, Iteration Builds Momentum. Design is a balance of doing, presenting, collecting feedback and collaborating with teams to push ideas forward. Great design happens when we build momentum with rapid design iterations.

Failure helps us get into a flow

Industrialized, rigid production processes aim to remove failure to create a consistent result. But this ultimately harms a designer's development and stifles creativity. The best design happens when we harness the power of failure to propel us forward. Far from being the enemy, learning to overcome failure is what fuels great design. It pushes us to solve HUGE problems, but it must be regulated.

Psychologically, increasing amounts of failure can crush people. Instead of taking on huge failures all at once, we break them into smaller, digestible chunks. Let's call that iteration. Teams can further help individuals overcome their own saboteurs as it relates to failure with structured debate. This regulates the pressure from growing too strong, keeping it at a healthy level. By keeping failures small and building up confidence by overcoming them as both individuals and teams, we create unstoppable momentum and get into a flow.

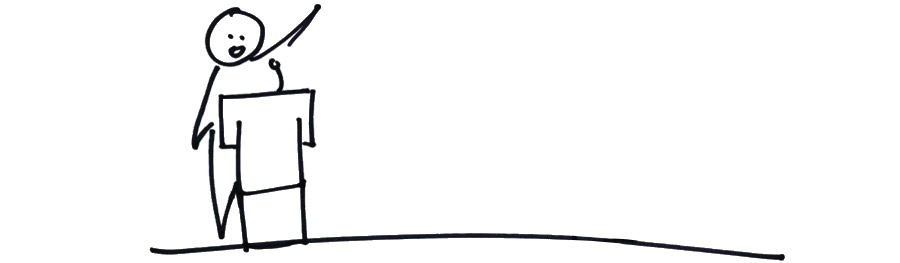

Don't do the big reveal

Steve Jobs was a masterful showman. With each successful product release, he made every company CEO jealous by ingraining the idea of "...and one more thing." The problem with this thinking, however, is that the surprise and delight of an Apple product release is not the same thing as magically arriving at that solution. When we see Apple doing the big reveal, this is a marketing technique, not a process to design a great product. We mistake the presentation approach with the design process to get to that idea. It's a psychological trick.

Designing for 'one best answer' isn't how great design happens. This design trapping is based on the idea of causal reasoning, "To the extent that we can predict the future, we can control it." states Saras Sarasvathy. Design agencies have perpetuated this concept for a century by removing the messy failures from the client engagement, and in doing so, obscure an important component of doing great work. The lack of a shared understanding of failure, and the pressure that comes with it, prevents teams from truly creating momentum together.

The big reveal leads companies to believe that with the use of a designer, they can arrive at a perfect solution through skills, reasoning and a plan. Most often this is not the case. In actuality, Steve Jobs pushed a highly iterative approach that sweated the details by consistently and constantly using a process of reduction to get to the essence of an idea with his team. Michael Lopp, senior engineering manager at Apple, described this as 10 to 3 to 1 as a process to get to one strong answer.

Get started with a volume of ideas

So if there isn't a single perfect answer, how do teams get started finding the best design answers? Start exploring ideas. Lot's of them. Producing in volume works because we can't predict what the final answer is going to be- we're creating a new reality by exploring the boundaries of an idea. Bill Hewlett said HP needed to make 100 small bets on products to identify six that could be breakthroughs. Sir James Dyson spent 15 years creating 5,126 failures to land on one that worked!

In fact, by producing in volume, the results can be fascinating. In one classroom experiment, a teacher challenged two sides of his class. Half of the class was tasked with creating 50 pounds of pots to get an A. The other half was tasked with creating a single, awesome specimen. The results showed that the half of the class that created in volume actually produced better pots. Students that produced in volume, and focused less on the craft, made incremental adjustments based on continuous learning.

Students that made adjustments based on their learnings let go of the assumption that there would be one perfect pot. There are many pathways to success through the process of effectual reasoning, which challenges the assumption that there is a perfect answer. Studies show that entrepreneurs have been using these techniques for a long time. The most successful entrepreneurs use this technique to filter through the volume of ideas to create momentum. They're able to do this because they know 'who they are', 'what they know' and 'whom they know'.

Momentum is created through small wins. It's a mindset

Creating in volume is necessary for iteration, but getting started can be the biggest challenge. Momentum requires an impetus. In design, we start creating by applying design methods. In sketching, that's finding a pen and paper. In code, it's jumpstarting the process by scaffolding with Foundation. We start by quickly removing barriers so the real work can begin.

So where does one start to find momentum in a design process? Sports is a great place to pull from- psychological momentum is defined as a state of mind where an individual or teams feel like things are going unstoppably their way. Success breeds success. Chris Myers further explains, "The impact is so strong, studies have shown that football coaches frequently change their overall behavior and adopt a more aggressive strategy after a single successful play early in the game."

Successful coaches are willing to accept small failures to gain this momentum. Relating this back to entrepreneurs and effectual reasoning, great coaches understand how to make these bets based on their skill limitations and team abilities. Coaches capitalize on small wins to create a favorable environment knowing that they can't completely control the outcome. This in turn creates a greater sense positivism within their teams and produces better results. Science backs this up through a concept called the As If Principle.

Structured debates through a repeatable process

If momentum requires small wins, creating an endless volume of ideas, however, won't dictate success. It's a start. Building momentum requires structure to keep creating product success. Again, the sports analogy is great for highlighting how to build a strong product team. Lebron James, the world's number one basketball player, started this past season with a losing team that eventually made it to the NBA finals. He described winning as a process:

We have to understand what it takes to win. It's going to be a long process, man. There's been a lot of losing basketball around here for a few years. So a lot of guys that are going to help us win ultimately haven't played a lot of meaningful basketball games in our league. When we get to that point when every possession matters , no possessions off -- we got to share the ball, we got to move the ball, we got to be a team and be unselfish -- we'll be a better team.

Teams must learn to create small wins through consistent collaboration and practice- it's a process. Creating great ideas through design collaboration isn't just about brainstorming. Nor is momentum created by designers just sitting around coming up with ideas (this is a fallacy based on the lone genius myth). It's structured debate with a team. And as Lebron points out, every possession matters.

Structured debate helps teams move a creative process forward and creative debates can happen in lots of different ways. Pixar uses the idea of Plusing where ideas are considered gifts, not something to close down. Feedback sessions are an opportunity to make your partner and team look good. Randy Nelson suggests that we shouldn't judge ideas- it's an opportunity for the creator to say, "here's where I am starting, " and the critiquer to add, "yes, and." What's important here is consistency and a culture that supports the approach.

Charlan Nemeth's research, on the other hand, suggests that the rule "not to criticize" another's ideas is distracting and actually has the unintended consequence of thwarting creative ideas. But rather than randomly critiquing a sketch or shooting down an idea, the general rule is that you may only criticize an idea if you also add a constructive suggestion. Daniel Gogek further expands on this approach:

Science backs up the idea that structured debate is far superior to simply brainstorming. A study led by UC Berkeley professor Charlan Nemeth found that when a team used structured debate, it significantly outperformed a team instructed to merely 'brainstorm.' Nemeth concluded that "debate and criticism do not inhibit ideas but, rather, stimulate them." What might be even more significant is that after the teams disbanded, the team that used structured debate continued to generate further ideas. It seems that the experience of a constructive debate lingers, and people continue to come up with new ideas.

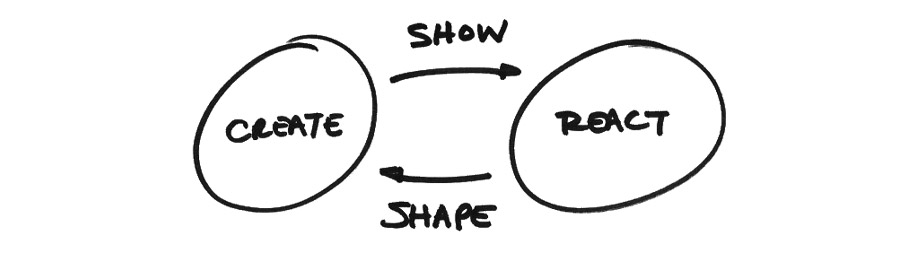

In Progressive Design, we've come up with a system that produces amazing results. We've synthesized the best practices through 1000's of design projects into The Design Feedback Loop which facilitates a simple and repeatable design process. Momentum requires a consistent feeding of ideas and feedback. Without learning, we get stuck in one place. By using the The Design Feedback Loop through the entire design process, teams can gain understanding of the problem through consistent practice to uncover better ideas. This iteration reveals opportunities and problems using both convergent and divergent thinking.

Failing fast helps us move forward

In theory, working through a repeatable process should consistently produce better results through practice. And indeed, it does. But creating great products also requires constantly dealing with changing circumstances- markets are dynamic, which means teams must continually challenge their assumptions. Challenging these assumptions feels risky and can reveal that teams might not have all the answers. But when we are willing to overcome these potential failures, growth and momentum happen.

Fail fast, one of our values at ZURB, provides everyone an opportunity to learn through failure. It also allows us the opportunity to keep moving forward when we perceive something to be a failure. Are we really trying to fail? No. We're making it acceptable to fail- it's a mental technique to help us push forward. John Maeda captured this recently in a tweet, "Fail fast" and "embrace failure" miss the fact that failing isn't the goal. "Recover fast" and "learn from failure" matter way more.

In design, failure itself isn't really the problem, it's getting over the mental impact. Richard Branson equates overcoming failure with addressing fear, "I've always found that the first step in overcoming fear is figuring out exactly what you're afraid of. In your case, I wonder: Is your anxiety a reflection of doubts about your business plan? Or is it rooted in your experience with your previous venture?" It's not as easy as just moving forward from failure, we need to recognize the wounds failure inflicts. Failure makes our goals seem tougher, our abilities seem weaker, damages our motivation, makes us risk averse, limits our creativity and eventually just makes us feel helpless. It's no wonder momentum is so hard to achieve.

But let's take this concept further- it's not just overcoming failure, it's embracing failure. "Achieving resilience in the face of failure, perseverance in the face of adversity is a central part of any ultimate success, and part of our own evolution, " says Agustin Fuentes Ph.D. Design teams must embrace the uncertainty of failure to truly create great products. They must push their companies to embrace Antifragility. Nassim Taleb states in his book Antifragile, "Firms become very weak during long periods of steady prosperity devoid of setbacks, and hidden vulnerabilities accumulate silently under the surface, so delaying crises is not a very good idea." Further, we must seek out failure, "When some systems are stuck in a dangerous impasse, randomness and only randomness can unlock them and set them free'by a mechanism called stochastic resonance, adding random noise to the background makes you hear the sounds (say music) with more accuracy."

What coping mechanisms do we have to help design teams embrace failure? Perhaps it's focusing less on the actual failure, and helping teams work more like entrepreneurs. In my experiences at ZURB, many employees believe my decision making is sometimes delusional- but I don't stress because many of these feelings are based on embracing failure as a way to fuel us forward. As it turns out, it's a thing. Saras Sarasvathy points out that we can only expect to move forward through small risk taking, something she defines as "affordable losses." She discovered seasoned entrepreneurs will tend to determine in advance what they are willing to lose, rather than calculating expected gains. Her paper explains how effectual reasoning emphasizes affordable loss.

Deliver better results by timeboxing

If embracing failure helps us drive a design process forward, timeboxing helps us keep our bets small so that our failures don't overwhelm us. Decisions are made faster by reviewing design work, even if the work is not polished. At ZURB, timeboxing helps us deliver better results by constraining our time and focusing on a goal in each phase of The Design Feedback Loop. This happens in small intervals over a few days. Timing depends on the scope of the design task.

Each small, defined design task provides an opportunity to build momentum by helping the team react to the lessons learned. Small iteration cycles give teams an opportunity to work through small failures and wins. Timeboxing helps us create focus and keeps the team constantly aware of the next deadline so each decision pushes us towards a goal.

Peter Sims determined it's better to make a bunch of small bets through his research of some of the most successful companies. Companies have figured out different ways to apply this concept to their design teams. Google uses a technique of design sprints to arrive at solutions in a fixed week. By making the expansion and closure of ideas happen together, Apple is able to create a type of timebox through a process of paired design meetings.

A design process in motion stays in motion

Getting a design effort started requires doing! And in large volume. We must not worry early on about getting to single, great answer. Instead, teams must optimize for small wins to help catapult themselves forward in the design process. Through a structured process of giving and receiving feedback, we can find the wins necessary to fuel our momentum and keep our design teams on the right pathway.

The Design Feedback Loop in Progressive Design helps us structure the creative debate. A solid design process can help us build momentum, but we also shouldn't overthink the process- instead focus on keeping momentum by overcoming obstacles and failure that stop iteration from happening. When we accept failure as a part of the design process, we truly put our team in a place to learn. Iteration is an endless endeavor in a design organization, but as part of a design process, we must learn to timebox to complete our work.

Bryan Zmijewski

Leading the charge at ZURB since 1998

Our fearless leader has been driving progressive design at ZURB since 1998. That makes him quite the instigator around the offices, consistently challenging both the team and our customers to strive to always do better and better.

Learn more →

Follow him at @bryanzmijewski